DOWNLOAD ——–>Semiotics Handout

Semiotics is concerned with meaning; how representation, (language, images, objects) generates meanings or the processes by which we comprehend or attribute meaning. The use of semiotic analysis challenges concepts such as naturalism and realism (the notion that images or objects can objectively depict something) and intentionality (the notion that the meaning of images or objects is produced by the person who created it; that is, the significance of images or objects is not understood as a one-way process from image or object to the individual but the result of complex inter-relationships between the individual, the image or object and other factors such as culture and society.

We say that semiotics is the study of signs and signifying practices. A sign can be defined, basically, as any entity (words, images, objects etc.) that refers to something else. Semiotics studies how this referring results from previously established social convention (Eco 1976, 16). That is, semiotics shows how the relationship between the sign and the ‘something else’ results from what our society has taught us. Semiotics is concerned with the fact that the reference is neither inevitable nor necessary. The image of the swastika, for example, can have radically different meanings depending on where and how it is viewed.

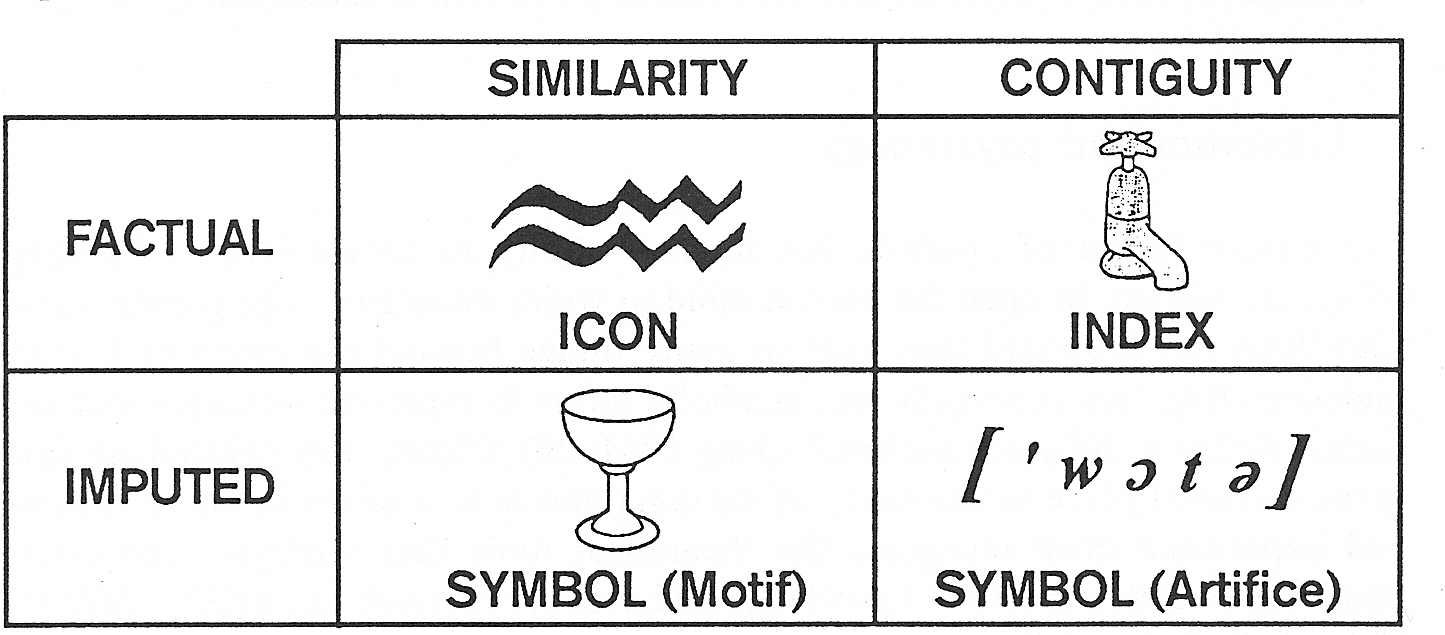

- An icon (also called likeness and semblance) is a sign that denotes its object by virtue of a quality which is shared by them but which the icon has irrespectively of the object. The icon (for instance, a portrait or a diagram) resembles or imitates its object. The icon has, of itself, a certain character or aspect, one which the object also has (or is supposed to have) and which lets the icon be interpreted as a sign even if the object does not exist. The icon signifies essentially on the basis of its “ground.” (Peirce defined the ground as the pure abstraction of a quality, and the sign’s ground as the pure abstraction of the quality in respect of which the sign refers to its object, whether by resemblance or, as a symbol, by imputing the quality to the object.[32]). Peirce called an icon apart from a label, legend, or other index attached to it, a “hypoicon”, and divided the hypoicon into three classes: (a) the image, which depends on a simple quality; (b) the diagram, whose internal relations, mainly dyadic or so taken, represent by analogy the relations in something; and (c) the metaphor, which represents the representative character of a sign by representing a parallelism in something else.[33] A diagram can be geometric, or can consist in an array of algebraic expressions, or even in the common form “All __ is ___” which is subjectable, like any diagram, to logical or mathematical transformations. Peirce held that mathematics is done by diagrammatic thinking — observation of, and experimentation on, diagrams.

- An index* is a sign that denotes its object by virtue of an actual connection involving them, one that he also calls a real relation in virtue of its being irrespective of interpretation. It is in any case a relation which is in fact, in contrast to the icon, which has only a ground for denotation of its object, and in contrast to the symbol, which denotes by an interpretive habit or law. An index which compels attention without conveying any information about its object is a pure index, though that may be an ideal limit never actually reached. If an indexical relation is a resistance or reaction physically or causally connecting an index to its object, then the index is a reagent (for example smoke coming from a building is a reagent index of fire). Such an index is really affected or modified by the object, and is the only kind of index which can be used in order to ascertain facts about its object. Peirce also usually held that an index does not have to be an actual individual fact or thing, but can be a general; a disease symptom is general, its occurrence singular; and he usually considered a designation to be an index, e.g., a pronoun, a proper name, a label on a diagram, etc. (In 1903 Peirce said that only an individual is an index,[34] gave “seme” as an alternate expression for “index”, and called designations “subindices or hyposemes,[35] which were a kind of symbol; he allowed of a “degenerate index” indicating a non-individual object, as exemplified by an individual thing indicating its own characteristics. But by 1904 he allowed indices to be generals and returned to classing designations as indices. In 1906 he changed the meaning of “seme” to that of the earlier “sumisign” and “rheme”.)

- A symbol* is a sign that denotes its object solely by virtue of the fact that it will be interpreted to do so. The symbol consists in a natural or conventional or logical rule, norm, or habit, a habit that lacks (or has shed) dependence on the symbolic sign’s having a resemblance or real connection to the denoted object. Thus, a symbol denotes by virtue of its interpretant. Its sign-action (semeiosis) is ruled by a habit, a more or less systematic set of associations that ensures its interpretation. For Peirce, every symbol is a general, and that which we call an actual individual symbol (e.g., on the page) is called by Peirce a replica or instance of the symbol. Symbols, like all other legisigns (also called “types”), need actual, individual replicas for expression. The proposition is an example of a symbol which is irrespective of language and of any form of expression and does not prescribe qualities of its replicas.[36] A word that is symbolic (rather than indexical like “this” or iconic like “whoosh!”) is an example of a symbol that prescribes qualities (especially looks or sound) of its replicas.[37] Not every replica is actual and individual. Two word-symbols with the same meaning (such as English “horse” and Spanish caballo) are symbols which are replicas of that symbol which consists in their shared meaning.[31] A book, a theory, a person, each is a complex symbol.

Apply – Icon / Symbol / Index to — WATER